PREVIOUS EXHIBITS: | LEONARD FREED: THE ITALIANS | KAITLYN 5x5

THE MILL CHILDREN | REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE

POWDER RIDGE - NADINE'S COUPLES - SUSANNAH'S PICKS

MIXED MEDIA | CULTURAL ICONS | ARTISTS WITHOUT BORDERS | NUDE & NAKED

ARTS OF WWII | JON ISHERWOOD | EVE SONNEMAN | LEONARD FREED

SPECIAL PROJECTS: HOOSAC RIVER LIGHTS

CONTACT | DIRECTIONS | MAILING LIST

EXHIBITIONS BEGIN JUNE 2011

Limited Edition Exhibition Print

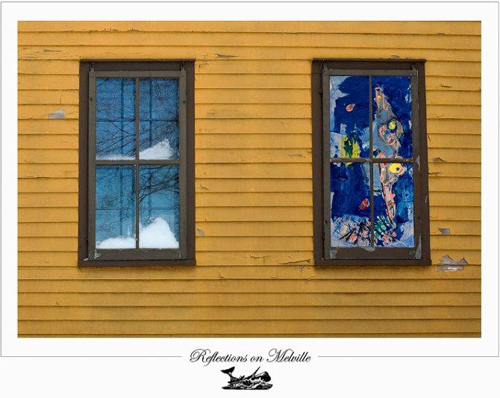

REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE

Limited to 200 Signed Prints, 24" x 30", 2011

Archival Digital Print on Heavy Weight Museum Paper

$200. Unframed plus Shipping and Handling.

|

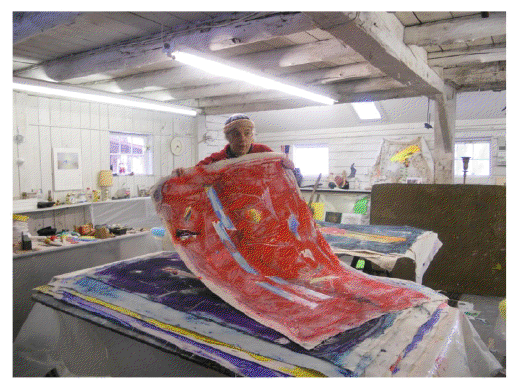

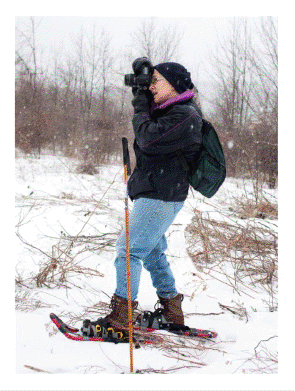

REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE  Arthur Yanoff in his Great Barrington Studio with Melville Paintings. All Rights Reserved. In 2010 I started a collaboration with Great Barrington based Abstract Painter Arthur Yanoff and Photographer Kay Canavino, who is based in Adams, MA. Yanoff wanted to tell the story of Herman Melville, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Monument Mountain through Photographs and Paintings. As we got into this project we drifted away from the MOUNTAIN OF THE MONUMENT theme and moved to REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE. This exhibition explores the relationships of Herman Melville to Arrowhead – his farm home in Pittsfield and to the surrounding country side. It also explores the personal and literary influences of Nathaniel Hawthorne on Melville and his vision of a Whale from the shape of Mount Greylock in winter. At Arrowhead all these forces came together for Melville with the resulting great American novel: Moby-Dick. The BRILL GALLERY of North Adams has selected a mix of this amazing results of almost 10 months of hard work during sweaty hikes up Monument Mountain to exploring Melville’s footsteps in the freezing cold to hours of interviews with experts on the local lore and customs, Melville’s life, the geology of the mountains, the role of the Mohicans in the region, etc. The results are some of the best art from these two professionals. We will be exhibiting many of these Photographs and Paintings at various venues in the Berkshires and beyond starting June 2011.  The Whale Rock by Kay Canavino. All Rights Reserved. In the 1800s, Sperm Whales were hunted down for their oil and ambergris. Whales were given names by the whalers – especially those that were difficult to kill or were particularly aggressive. In 2010, the Williams College Museum of Art in Williamstown exhibited Tristin Lowe’s huge soft sculpture Mocha Dick – a takeoff of the very dangerous albino Sperm Whale known for sinking 5 ships and killing more than 30 sailors off the coast of Chile. It is believed that Herman Melville got the name Moby-Dick from reading some of these accounts. It is further believed that Melville saw the image of a white whale while gazing at the snow covered Mount Greylock from his Arrowhead study in March 1851 – “like a snow hill in the air.” Ten years earlier, Melville had sailed on board the whale ship, Acushnet, to the Pacific so, he knew personally many of the details of a whaler’s life. For Melville, the ship, Pequod, became the mirror of the world as he knew it. He was against slavery, probably experienced same-sex relationships, probably felt some guilt about the treatment of Native Americans, knew something about the Unpardonable Sin, etc. In the end, only the sailor named Ishmael survives Moby-Dick’s attacks. It was he who tried to see other points of view where his captain Ahab destroys himself in his single-minded purpose of turning Moby-Dick into a dead oil well. Our starting point was 5 August 1850 when Melville met Nathaniel Hawthorne for the first time during a hike and picnic up Monument Mountain in Great Barrington. Melville discussed his literary projects with Hawthorne, and was encouraged to advance his whaling stories into a book. The two became best friends during this period, and Melville acknowledged Hawthorne by dedicating Moby-Dick to him. The manuscript was written on paper produced at the Crane Paper Mill in nearby Dalton.  Kay Canavino pursuing Melville All Rights Reserved. It became clear to us that Melville and his characters saw whales everywhere. We too found visions of whales and whalers’ tools during our hikes and these visions show up in the Artists’ Photographs and Paintings. In Moby-Dick Ishmael evaluates the visual representation of whales : “I shall ere long paint to you as well as one can without canvas, something like the true form of the whale as he actually appears to the eye of the whaleman.” Over the past hundred years many artists have taken this challenge, including Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Sam Francis, Frank Stella, Leonard Baskin, and Rockwell Kent . They have all tried to imagine Moby-Dick in their art – and so have we in REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE. Melville spent 13 years at Arrowhead. Although there were some high points and good times there was also an unhappy home life, bouts of depression and lots of financial pressures. We tried to connect with this tension. By 1850 Melville clearly needed a publishing success. It is believed that during his friendship with Hawthorne, he was influenced by their talks and additional readings of Shakespeare. The final manuscript of Moby-Dick was sent to his publisher in England as The Whale in October 1851 and then a month later to his New York publisher Harper & Brothers. The book got some good reviews, but it did not sell well. Under mounting pressures Melville returned to New York City in 1863 and took a job as a Customs Inspector. On the side he gave lectures and wrote poetry. Melville died in 1891 at the age of 72. It was not until about 1925 that scholars realized the genius of Moby-Dick and Melville’s place as one of America’s greatest writers. This is our celebration of the 160th anniversary of the publication of Moby-Dick. Canavino and Yanoff, as artists, spent the past months searching for their own elusive whale. Arthur Yanoff has also dedicated his Paintings to the memory of his dear friend Paul Metcalf. Metcalf, a writer and resident of the Berkshires was Melville’s great grandson. We will be exhibiting about 30 Photographs and Paintings in the Barn at Arrowhead in Pittsfield. Another different group of about 30 pieces by these same artists will be exhibited at the Eclipse Mill Gallery in North Adams from 24 June to 7 August 2011. We are planning that REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE will travel to other whaling and art museums.

BRILL GALLERY PRODUCTIONS

REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE “Now, for a house, so situated in such a country to have no piazza for the convenience of those who might desire to feast upon the view, and take their time and ease about it, seemed as much of an omission as if a picture-gallery should have no bench; for what but picture-galleries are the marble halls of these same limestone hills? – galleries hung, month after month anew, with pictures ever fading into pictures ever fresh.” - Melville in The Piazza In 2010 artists Kay Canavino and Arthur Yanoff, influenced by Herman Melville’s writing of Moby-Dick at Arrowhead - his home in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts - set out to document in photographs and abstract paintings the landscapes and personalities that inspired what is arguably one of the greatest American novels of all time. The view of Mount Greylock, seen through Melville’s study window, was the inspiration for the great white whale in Moby-Dick. But, the whole Berkshires region seems to have been cathartic for Melville, a notorious intellectual loner. Nature seems to have functioned not only to inspire his art but as a sort of surrogate religion for him. Many of Melville’s letters to Nathaniel Hawthorne (whom he met in the Berkshires during the famous Monument Mountain picnic in 1850 and to whom he dedicated Moby-Dick) suggest his reluctance to embrace conventional religion and his consequent willingness to submit himself to the beauty that surrounded him.* In one such letter, Melville dismisses Goethe’s famous saying “Live in the all” as flummery but he continues “This “all” feeling, though, there is some truth in. You must have often felt it, lying on the grass on a warm summer’s day. Your legs seem to send out shoots into the earth. Your hair feels like leaves upon your head. This is the “all” feeling”. Additionally, in the novel Israel Potter, Melville describes the area surrounding Arrowhead in religious terms: “the balmy breeze… like a censor, the…dome of Taconic…like St. Peter’s and the twin summits of Saddleback the two-steepled natural cathedral of Berkshire”. What Melville is describing here is what many Berkshires lovers have experienced – nature as religion. This concept of nature as religion; nature as something greater than one’s self, has well established literary and pictorial origins. The literary origins of the idea lie in the eighteenth century appreciation of the fearful and irregular forms of external nature; a concept referred to as the sublime. The sublime is most famously defined by philosopher Edmund Burke as something that strikes awe and terror into the heart of the viewer. According to Burke, in the realm of the sublime, we may approach the highest Being and power, the Deity whose “first, most natural, and most striking effect” is terror. By the nineteenth century, this sublime quest had become inextricably entangled with a religion of nature enunciated by the most influential of Melville’s contemporaries. The pursuit of a benign Deity accessible in nature was essential to these writers. The experience of the infinite in nature provided them reassurance of the sustenance of order in the face of chaos. The terrible quest of Ahab for the great white whale may be identified with this quest for the sublime, but in Moby-Dick the effect of the sublime is terror without reassurance. Melville, then, was critical of the optimistic advocates of the sublime quest even as he admired them.** Burke’s first example of sublimity, the sea, is the setting for almost the entire narrative of Moby-Dick. The sea is sublime due to its vast extension and depth, its rugged and broken surface and the apparent infinity in the succession of its waves – a phenomenon captured expertly by Canavino in Waves of Time. In Yanoff’s Moby’s Whirlpool and Connections to the Sea we also perceive something of the sea’s irresistible power and obscurity; the same irresistibility that drove the Pequod and her sailors. Among all creatures, Burke sights the whale as sublime. Accordingly, Moby-Dick’s Ishmael praises whales as universal sources of astonishment, awe and reverence. Moby-Dick himself is the epitome of the sublime whale. In all his appearances in the novel he is sublime to the highest degree, a monarch and a god, but he is not the benign Deity Melville’s contemporaries sought, he is powerful and terrible in his “unexampled intelligent malignity.” Something of Moby’s awesomeness and terrible power is evident in Canavino’s and Yanoff’s Whale Rock images. Artists of Melville’s period were similarly drawn to the sublime qualities of nature. From John Constable’s quiet documentation of the picturesque English countryside to JMW Turner’s more sublime depictions, many artists have made something of a religion out of their renderings of the land. The remarkable abstract paintings by Arthur Yanoff on view in this exhibition may be seen as the culmination of this Romantic pictorial tradition that placed a premium on emotional expressiveness, broad loose brushwork and rich warm color. Images like Melville’s Dream at Arrowhead and Rapture of the King with their largeness of scale, their vastness and their grandness, certainly seem to be concerned not with the mystery of individual feeling or personality but with the mystery of the world. They seem to dig into the metaphysical and to that extent to seek the sublime. But for Yanoff, as for Melville, the quest for the true sublime; for union with something larger than one’s self, is wrought with peril. In embarking on this project, Arthur Yanoff was consumed by the notion of “The Unpardonable Sin” which in Hawthorne’s short story Ethan Brand is defined as “The sin of an intellect that triumphed over the sense of brotherhood with man and reverence for God.” Yanoff describes it as “Individuals suffocated by their self-absorption, setting themselves apart from mankind, driven solely by their own singularity.” In other words “The Unpardonable Sin” is artistic/intellectual/individual egotism. The same egotism that resulted in the demise of Captain Ahab and Ethan Brand; that haunted the minds of Melville and Hawthorne is still alive and well today. Yanoff describes needing to struggle against this “sin”, needing to engage his own time in order to succeed in his quest for the true sublime. Ironically, for all these artists the Berkshires are both the inspiration for their art – thus feeding the ego and fueling “The Unpardonable Sin” and a respite from it. While Yanoff creates with something of the sublime – his paintings deliver something of the awe and force that Burke spoke of - Canavino more quietly documents the picturesque. The literary origins of the picturesque also lie in the eighteenth century. The term entered the English cultural debate as a mediator between the opposed ideas of rationally idealized beauty and the sublime. In the last third of the eighteenth century picturesque hunters began making sketches using “Claude Glasses” – tinted portable mirrors to frame and darken the view. These artists too appreciated the irregular forms of external nature. They were interested in capturing wild scenes and in fixing them as pictorial images. Canavino photographs with the eye of a painter. Indeed the English term picturesque is derived from the Italian pittoresco meaning “in the manner of a painter”. Images such as Waves of Time and Violent Sea carefully mimic the compositional devices of “pictures”; their closely cropped perspectives capable of turning stone into water. These images are designed with “counterfeit neglect”; they are carefully designed to look natural. But Canavino’s images also brush up against the sublime in several instances such as the hauntingly beautiful Night Thoughts at Arrowhead and Unpardonable Sin where we are instilled with a degree of horror by what is dark, uncertain and confused. Canavino’s and Yanoff’s quest for the true sublime; for union with something larger than one’s self - ultimately eluded Melville. The fear that kept Melville from joining his contemporaries and “living in the all” was the fear of losing his individual artistic self to the collective. Melville was first and foremost the consummate artist - guilty of the “Unpardonable Sin” - and this is what kept him from fully embracing the sublime quest. As Hawthorne would later say, Melville could “neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he [was] too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other”. As for Canavino and Yanoff, the quest is still in progress. The future is still uncertain. Samantha Pinckney, Curator *Hershal Parker in his biography of the writer makes it clear that Melville became a nominal member of the Unitarian Church only to placate his wife. See Hershal Parker’s Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume II, 1851-1891. **The idea that Melville’s sublime quest was ultimately doomed comes from Barbara Glenn’s “Melville and the Sublime in Moby-Dick,” American Literature, vol. 48, no. 2 (1976), pp. 165-182 REFLECTIONS ON MELVILLE EXHIBITS MELVILLE AND MOBY-DICK AT ARROWHEAD HERMAN MELVILLE AND NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE THE BERKSHIRE COUNTRYSIDE AND HERMAN MELVILLE Artists' Biographies Click here to read the article in Berkshire Fine Arts |